This short documentary gives an overview of efforts in the field of area informatics to visualize and predict area conditions through quantifying various related data

Area studies has a long history of collecting a wide range of materials and data from all over the world. Digitization and computational data analysis are indispensable to using these materials and data when conducting area studies research. Area informatics therefore develops tools to support the processing of large amounts of data.

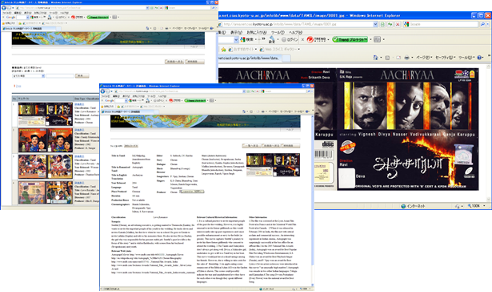

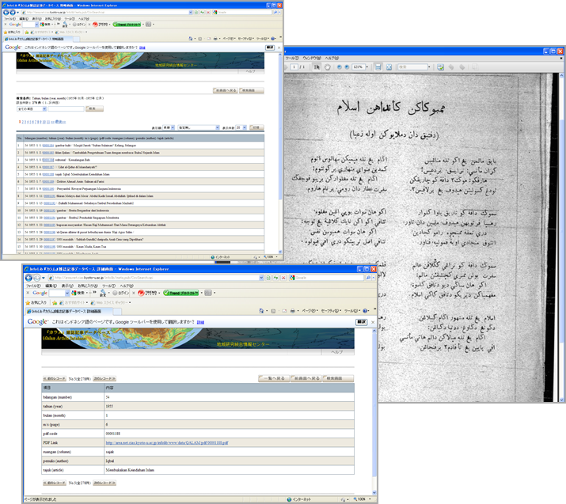

In its initial stages, area informatics research and development focused on digitization methods, metadata creation, and database tools to store and use digitized data (see notes 1 and 2). We created two such tools, namely My Database and the Resource Sharing System. Building a database needs expert knowledge and skills about database systems, server devices, network devices, and so on. Therefore, My Database is an information tool devised so that even researchers who do not have such expert knowledge and skills can build databases with simple operations. The Center for Southeast Asian Studies has about 100 databases, both public and private, and most of them are built and maintained with the My Database (https://kyoto.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/collections/#db) tool. The Resource Sharing System is a tool that allows users to collectively search area studies-related databases on the Web. Users can retrieve about 50 databases related to area studies in Japan and overseas at once. Using a computerized translation mechanism, keywords in various languages can be inputted to search for databases (http://app.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/GlobalFinder-lg/cgi/Start.exe).

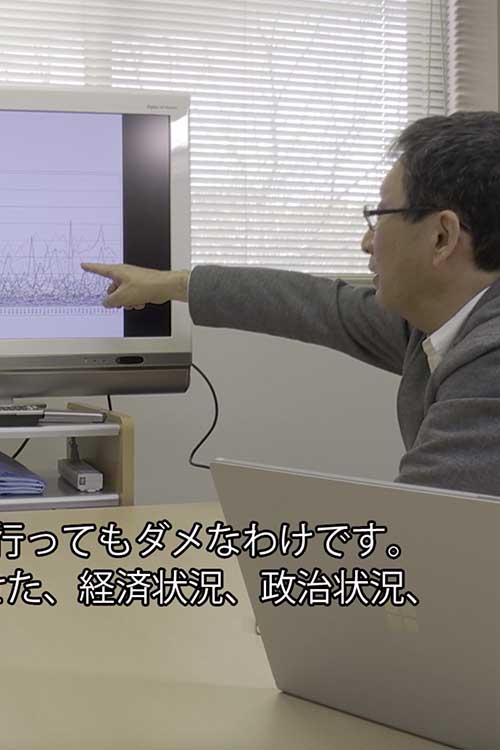

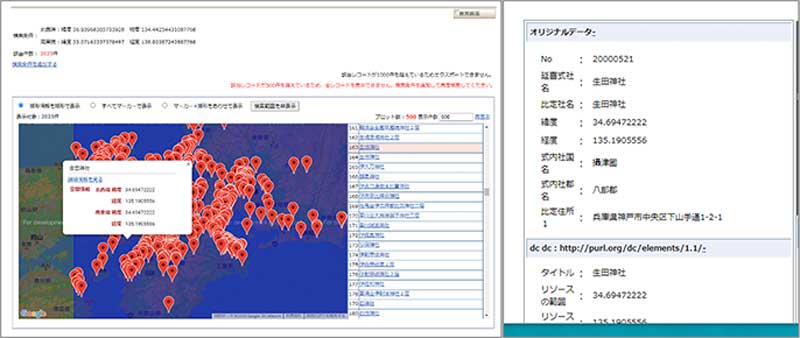

Keywords are essential when searching for information from ordinary databases. The location and time stamps of information are also critical in searching and organizing data (such as when making maps or chronological tables). Therefore, in the second stage of area informatics, we are developing visualization and analysis tools using the software GIS (Geographic Information System) and Timeline. For example, we have produced spatiotemporal tools that can convert a place name to its latitude and longitude and convert the Japanese calendar to the Gregorian one (see notes 3, 4, and 5).

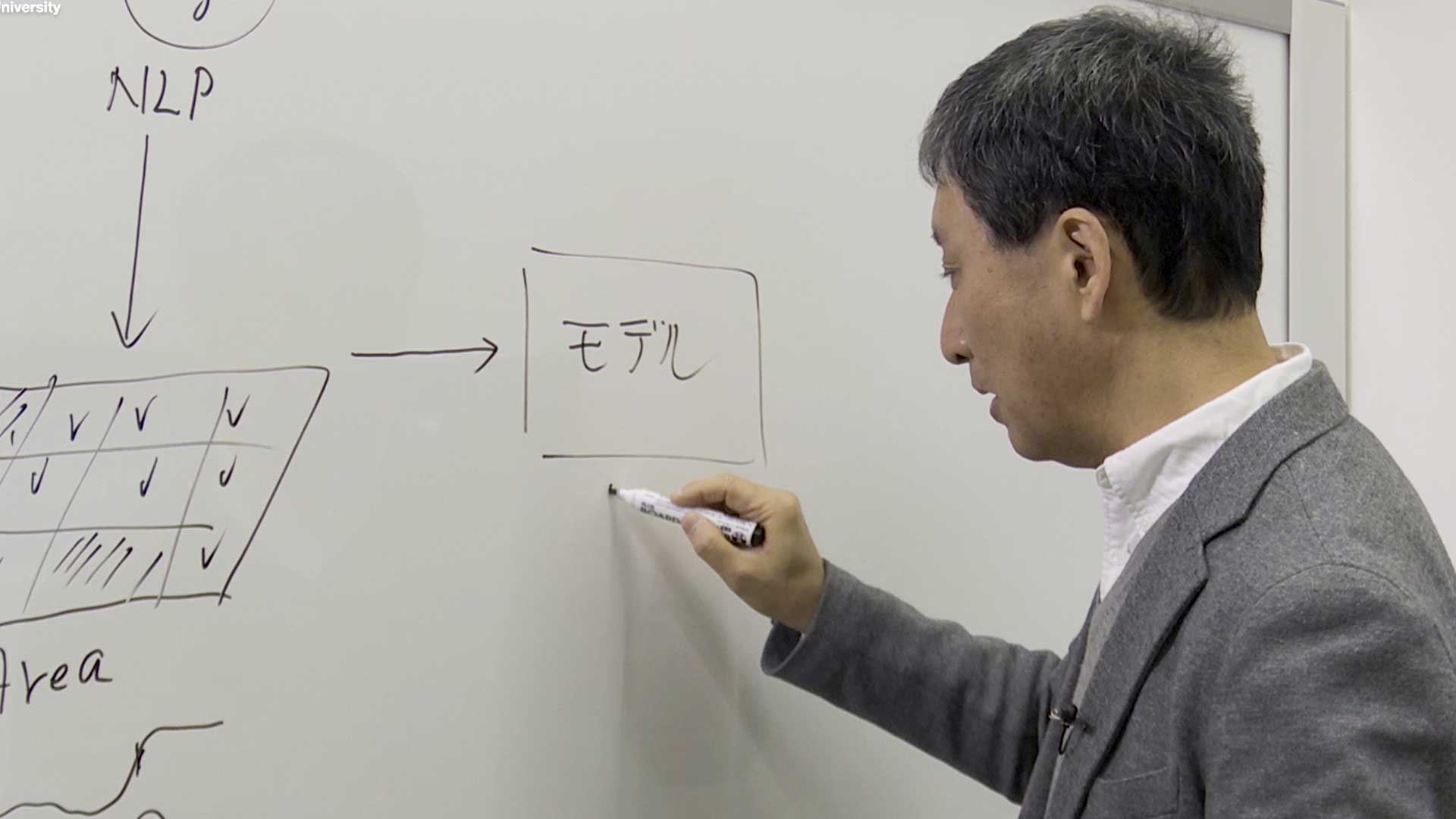

Due to the rapid development of information technology (IT), including the use of the Internet since the 1990s, a substantial amount of qualitatively rich information about local areas has been exchanged in real-time on the Web and through SNS, and satellites and monitoring sensors constantly generate big data such as consistently collected datapoints on environmental conditions. Exchange of such data is particularly notable when a large-scale disaster such as an earthquake or tsunami occurs or when a national election is held. Even in area studies, big data available on the Internet is becoming indispensable for research. On the other hand, with the continuous improvement of computer processing power and the advent of new information processing technologies such as artificial intelligence, it has become possible to better understand the depth and scale of problems that have until now been difficult to calculate. Therefore, as a third stage of area informatics, we are struggling with the challenges of 1) visualizing the state or conditions of an area by applying natural language processing and machine learning to big data available on the Internet, and 2) predicting future outcomes based on historical and existing trends in an area by combining models and simulations (for example predicting the effects of implementing a certain policy). While we are not sure of our ultimate outcomes or even what success will look like, I am certain that area informatics is an important research theme.